By Katheryn Yetter, Esq.

In 1986, several events took place that reflected the culture and technology of the time: the Internet Message Access Protocol was designed, opening the door to the widespread use of email; Voyager completed the first nonstop circumnavigation of the earth by air without refueling; the first ten Rock and Roll Hall of Fame artists were inducted; and, The National Judicial College (NJC) offered a course entitled Dispute Resolution Skills (DRS) for the first time.

By and large, theories and practices relating to dispute resolution in the late 1970s and early 1980s focused on conflict management outside the courtroom. However, in 1986, court-mandated mediation and statutory arbitration were trending on the legislative front, models for appropriate alternatives to trial were emerging, and judges were hungry for information and tools. After a nationwide assessment of judges’ needs, the NJC determined that an ideal course would include information on the various modes of dispute resolution, setting up programs in courts, methods specific to case type, and judicial ethics implications. The resulting DRS course was so popular that in 1986, it was offered three times to a total of 141 judges.

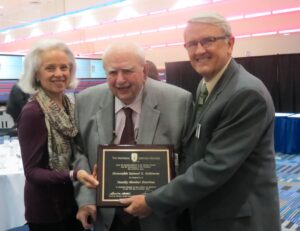

As DRS gained momentum among the judicial community, a New Jersey judge named Samuel DeSimone (or “Big Sam” to his colleagues) adopted it and helped the NJC further refine the core competencies of dispute resolution skills for judges. “Big Sam was instrumental in bringing the judicial perspective to a topic area that on its surface, may appear to appeal to non-judicial practitioners,”said Joy Lyngar, Chief Academic Officer at the NJC. “Since its inception, the NJC has offered continually improved versions of the course thirty-eight times and has tailored the curriculum for state court judges, administrative law judges, and tribal court judges.”

Big Sam joined the distinguished ranks of emeritus faculty for the NJC in 2012 after 25 years of teaching. “DRS is a better course because of his vision and dedication,” said Lyngar.

Where once ADR stood for “alternative” dispute resolution (i.e., that which occurred outside of the courtroom), ADR is now thought commonly to stand for “appropriate” dispute resolution, whether in or out of court. No longer are the skills used for mediators or arbitrators outside of the courtroom setting. The skills that are required in practicing ADR are essential to a judge who finds him or herself needing to negotiate, conduct settlement hearings, refer to mediation, or one who chooses to become a private or state-appointed arbitrator once he or she leaves the bench. As the course continues to evolve, the NJC hopes to honor Big Sam’s legacy by continuing to offer a Dispute Resolution Skills course that appeals to a judiciary invested in holistic problem-solving in a 21st century court system.

Katheryn Yetter, Esq., is the Academic Director for The National Judicial College. She can be contacted at The National Judicial College, Judicial College Building/MS 358, Reno, NV 89557; 775-327-8213; www.judges.org