by Gina Jackson, Permanency Planning for Children Department (NCJFCJ)

Working together to provide safety, permanency, and well-being are high priority goals that child welfare systems strive to achieve. It has been 33 years since the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) was passed, and it is important to take the time to evaluate the impact on the child welfare system since that time. How are we doing as a Nation in following this important law, in spirit and practice? Recently, there has been a surge in ICWA awareness due to the latest disproportionality reports and media coverage indicating that there is still a significant problem.

In the preamble of ICWA, 25 U.S.C. §§ 1901, Congress acknowledged that:

An alarmingly high percentage of Indian families are broken up by the removal, often unwarranted, of their children from them by non-tribal public and private agencies and that an alarmingly high percentage of such children are placed in non-Indian foster and adoptive homes and institutions; and states, [in] exercising their recognized jurisdiction over Indian child custody proceedings through administrative and judicial bodies, have often failed to recognize the essential tribal relations of Indian people and the cultural and social standards prevailing in Indian communities.

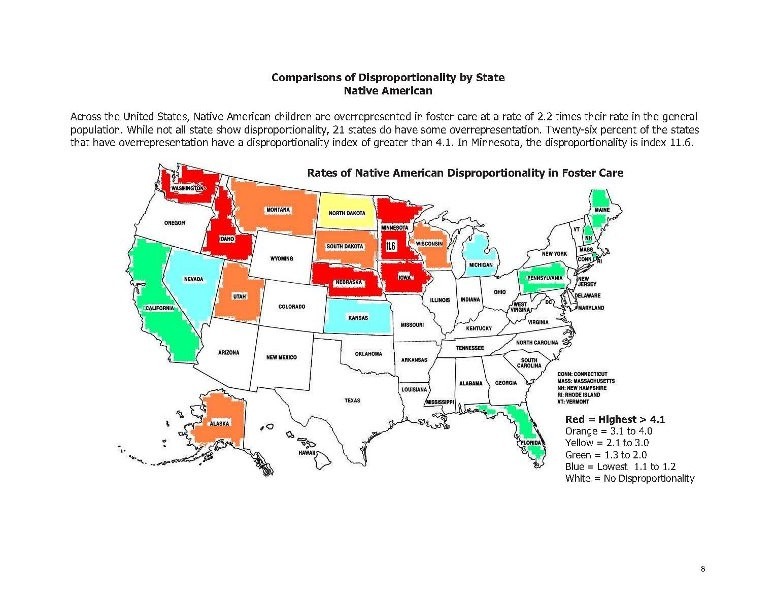

While there has been progress since ICWA was passed, disproportionality rates continue to remain high. A review of the child welfare system data indicates that “across the United States, Native American children are overrepresented in foster care at a rate of 2.2 times their rate in the general population” (Disproportionality Rates for Children of Color in Foster Care, published by the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges, May 2011). It is clear that many, many states continue to struggle with this issue, as 26% of states have a disproportionality index higher than 4.1., including one state that has an index rate of 11.6, which ultimately means that Native children come into foster care 11 times more often in that particular state. To download a complete copy of Disproportionality Rates for Children of Color in Foster Care, visit www.NCJFCJ.org.

It is time for leadership and vision from the bench to fulfill the ICWA promise. Since no child enters or leaves the child welfare system without a judge’s order, it is imperative for judges to not only have a solid working knowledge of the Indian Child Welfare Act, but an understanding of why we have the Indian Child Welfare Act. It is extremely important to learn from the past in order to build a very different future in working with Native children, families, and tribes.

The approach to tribal engagement and working with tribes should come from a place of honor, respect, and mutual learning. During the 2010 White House Tribal Nations Conference, President Obama shared this statement:

We know that, ultimately, this is not just a matter of legislation, not just a matter of policy. It’s a matter of whether we’re going to live up to our basic values. It’s a matter of upholding an ideal that has always defined who we are as Americans…and I’m confident that if we keep up our efforts, that if we continue to work together…we will achieve a brighter future for the First Americans and for all Americans.

It was during this conference, the U.S. announced it will sign the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. While the Obama Administration was meeting with tribal leaders, the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges (NCJFCJ) brought together a group of Tribal Judicial Leaders and other Model Court Lead Judges for an unprecedented gathering. The purpose of this gathering was to listen, gain insight, and ultimately seek guidance through a tribal perspective on effective outreach and inclusion of tribal courts in NCJFCJ’s work.

In the NCJFCJ’s governance structure, the organization has committed to weave diversity through everything the organization does. As a result of the first gathering, resolutions were developed and passed, including the NCJFCJ’s Resolution in Support of Tribal Courts. This resolution acknowledges Tribal Courts as “equal and parallel systems of justice”. The Conference of Chief Justices also passed a resolution in response to the gathering to “encourage greater collaboration between state courts and tribal courts to protect Native American children.” These resolutions reflect a commitment and call to action for state and tribal courts to work together as allies for children and families. Full texts of the resolutions can be found on the NCJFCJ Website.

The energy, ideas, and relationships developed in this group are remarkable. New state court and tribal court collaboratives are emerging. New state/tribal judicially focused ICWA workgroups are forming, integration of tribal judicial presence on state Court Improvement Program advisory groups is increasing, and cross-site court visits between tribal courts and state courts are occurring for mutual learning.

New ideas for pilot projects such as joint jurisdiction tribal/state courts are being discussed, as well as ideas for utilizing technology to better serve children and families. New judicial tools to improve ICWA performance are currently under development. Judges can make a difference by exercising their leadership and forming collaborative groups to strategically increase ICWA compliance on a local level and by working closely with State Supreme Court Improvement Programs to ultimately make an impact statewide. The following are just some of the things judges can do to provide judicial leadership to improve ICWA performance:

- Commit to a vision of 100% ICWA compliance with child welfare system stakeholders, involving tribes working collaboratively to begin a strategic plan of action.

- Ensure judicial officers and system stakeholders are effectively trained on historical trauma and institutional bias, as well as the spirit and context of the legislation.

- Engage tribes by developing authentic relationships, judge to judge, court to court, and system to system to solve issues.

- Invite tribes to participate on current teams, workgroups, projects, initiatives, training opportunities, and as valued partners.

As judicial educators and judicial leaders, you have an opportunity to bring knowledge, awareness, and to inspire a vision for judicial leaders to fulfill the ICWA promise. This will have a transforming effect on so many lives, not only for the children and families before the court, but for generations to come.

For more information or to receive resources, tools, and technical assistance, visit the following Websites:

- National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges: http://www.ncjfcj.org

- National Resource Center on Legal and Judicial Issues: http://www.apps.americanbar.org/child/rclji/home.html

- National Resource Center for Tribes: http://www.nrc4tribes.org/

- National Indian Child Welfare Association: http://www.nicwa.org

- Tribal STAR, a program of the Academy for Professional Excellence, San Diego State University School of Social Work: http://theacademy.sdsu.edu/TribalSTAR

- American Indian Enhancement Project of California Toolkit: http://calswec.berkeley.edu/CalSWEC/AIE/AIE_home.html

- QUICWA Compliance Collaborative Project: http://www.d.umn.edu/sw/cw/2010video/2011docs/QUICWA/brochure.pdf

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Gina Jackson, MSW, is a Model Court Liaison for the Victims Act Model Court Project with the Permanency Planning for Children Department of the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges working with several jurisdictions across the country. Ms. Jackson belongs to the Temoke Western Shoshone Tribe. She holds a Masters and Baccalaureate degree in Social Work from the University of Nevada, Reno, with a minor in Early Childhood.

Gina Jackson, MSW, is a Model Court Liaison for the Victims Act Model Court Project with the Permanency Planning for Children Department of the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges working with several jurisdictions across the country. Ms. Jackson belongs to the Temoke Western Shoshone Tribe. She holds a Masters and Baccalaureate degree in Social Work from the University of Nevada, Reno, with a minor in Early Childhood.

Ms. Jackson came to the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges from the University of Nevada, Reno School of Social Work, Nevada Training Partnership. She worked as a curriculum developer and statewide child welfare trainer during Nevada’s Program Improvement Plan (PIP) process. She also has experience as a child welfare caseworker and has done investigations, case management, adoptions and foster care licensing. She has been an instructor for the University of Nevada, Reno School of Social Work on and off for the past decade.

As a Model Court Liaison, Ms. Jackson hopes help improve the outcomes for abused and neglected children and their families across the country in implementing and sustaining systems change and best practices while being mindful of cultural differences and equity in treatment as a standard in our nation’s child welfare system.