By Nancy Smith, Field Trainer, Pima County Superior Court, Tucson, Arizona

Knowledge is of no value unless you put it into practice. – Anton Chekov

As judicial educators, we focus on how to present important topics to the judiciary in ways that not only inform them, but also assist them in changing practices which at times are deeply ingrained in judicial tradition and legal practice. When considering how to teach procedural fairness, Washington state judicial educators searched for a way that extended beyond the traditional conference plenary session so commonly used in our state. We sought to do more than inform, but also to convince people to change.

Adult learning theory teaches that adults learn better when they see both the extrinsic and intrinsic value of what they are being taught, when the topic is relevant to their work, and when they get to practice what they are learning. We also know that chunking a topic into easily digestible pieces and spreading learning out over time helps. This article describes a recent learning series on procedural fairness executed using a blended model in Washington State, following those adult learning precepts.

Procedural fairness concerns the public’s perception of how they are treated by the judicial system. Studies have shown that the perception of unfair or unequal treatment in the courts is the most important factor in public dissatisfaction with the American legal system (Burke and Leben, 1). If court users feel that they have been treated fairly, they are more likely to accept the outcome of their case, even if they lose. Judges and lawyers are concerned with fair legal outcomes—did the defendant get what he deserved? The public, on the other hand, is more concerned with whether they were treated fairly from a procedural standpoint—was the decision arrived at using fair methods? Professor Tom Tyler describes four key components to procedural fairness:

- Voice – Court customers expect to be able to express their viewpoint, or their side of the story.

- Neutrality – Court users believe that decisions are made consistently based on sound legal principles by unbiased decision makers.

- Respect – Individuals are treated with dignity and their rights are protected.

- Trustworthy authorities – Authorities care about the individuals before them and listen carefully to what they say. They address litigant’s needs by explaining decisions. (Burke and Leben p. 6)

The need for procedural fairness begins at the courthouse door (or on the courthouse web page) and permeates many aspects of the administration of the courts, as well as what occurs in the courtroom. Thus, things like good signage, a useful website, and helpful staff impact procedural fairness, as does what actually occurs when the defendant stands in front of a judge during hearings and trials.

For more information about procedural fairness, what it means and how it affects courts, please go to the Procedural Fairness website.

In order to understand how a blended learning model can be applied to the topic of procedural fairness, it is important to know what blended learning is. According to the Sloan Consortium, blended learning consists of courses or programs in which 30%-79% of the learning is offered online while the rest is face-to-face (Allen, Seaman, and Garrett, p. 5). The online portions and the face-to-face portions can be combined in whatever order best fits the learning objectives of the program. Online segments can be webinars, self-paced elearning, web-based research and activities, wikis, blogs, email and much more. Face-to-face portions can be lectures, workshops, seminars, discussion groups, or experiential learning modes such as field trips and interviews. For a longer discussion on a blended learning model for the courts, see Smith, N., Blended Learning: Seven Lessons Learned through Experience in the August 2012 NASJE News.

In Washington, we sought to put together a blended learning series that incorporated many best practices for adult education. Based on input from our diversity committees, our education committees and two Supreme Court commissions, we knew the material was important and relevant to our intended audience of judges and court administrators. We looked for methods to chunk the content, spread the learning out over time, offer opportunities to practice what was being taught, and provide practice activities to be able to self-assess progress. Ideas for the learning series are based on the model Context-Challenge-Activity-Feedback, as explained by Ethan Edwards at Allen Interactions (Edwards, p. 6). In short, and in the context of eLearning, Edwards counsels instructional designers to provide a relevant, work-related context for the learning design so learners’ interest is heightened. He suggests providing realistic challenges for learners, and interactive activities to allow them to practice solving the challenges. Finally, he advises providing feedback that offers guidance to the learner, not just “you’re right” or “incorrect, try again.”

To accomplish these goals and decide on learning modes that provided the necessary context, challenge, activity and feedback, several questions needed answers.

- In what order and in what time frame should the various parts of the program be presented. (context)

- What groups in the court community would serve as resources and planners for the program? (context)

- Who could be the respected expert(s) to meet judicial officers face-to-face and teach the topic? (context)

- What did judicial officers need to know prior to the face-to-face session, if anything? (context)

- How would judicial officers and court administrators know how they were doing with respect to procedural fairness? How could they measure their current and future status? (activity, feedback)

- What concrete steps could judicial officers take to be able to see themselves through the public’s eyes in the courtroom? (activity)

- Could judges be persuaded to take concrete steps? How could they be persuaded of the value of the steps? (challenge)

- How could judges measure their progress in their courtrooms? (activity, feedback)

- How could judges and court administrators measure progress in their courthouse? (activity, feedback)

One question we did have to answer was how to fund the project. The Washington Courts Blended Learning Project, a grant from the State Justice Institute, provided funds.

We found a willing expert and advocate in Judge Kevin Burke of Hennepin County Courts in Minnesota. Judge Burke has conducted research on the topic and written a white paper and other articles about it, as well as speaking nationally. His passion for the topic served as an inspiration for the Washington Courts educators involved in the project.

With Judge Burke on board, we were able to enlist the help of the Washington Supreme Court Minority and Justice and Gender and Justice Commissions. The Diversity and the Education Committees of the District and Municipal Court Judges’ Association and the Equity and Fairness Committee of the Superior Court Judges’ Association all climbed on board the project train early in the process. As it turned out, the judges on these committees really took a big risk later in the project to make it real to the audience, as you will see later. Washington Court Education Services educator Nancy Smith and several support staff completed the project team. The importance of buy-in from the various commissions and committees cannot be overstated in establishing the legitimacy of the project.

We decided on a four- or five-part learning series:

- Part One: Read the Burke/Leben white paper called Procedural Fairness: A Key Ingredient in Public Satisfaction.

- Part Two: Complete a Web-based Self-Assessment to measure procedural fairness throughout the court house.

- Part Three: Attend a face-to-face session at spring conferences with Judge Burke and Washington judges as faculty.

- Part Four: Participate in a webinar: Procedural Fairness: Real Steps for Real Improvement; facilitated by Judge Burke, with faculty from Washington State.

- Part Five: Repeat the web-based self-assessment to monitor progress. This part is optional, but encouraged.

To begin the series and establish a context for the topic, a lesson on the basics of procedural fairness was essential. We chose Procedural Fairness: A Key Ingredient in Public Satisfaction, a white paper of the American Judges Association written by Judge Burke and Judge Steve Leben as our basic “text.” Reading this article would help judges to understand what is meant by procedural fairness and how good techniques in this area could impact not only their workload, but also compliance with court orders, while also increasing public satisfaction. The article also cites sociological research on the topic, thus providing credibility about the value of the concepts put forth. We provided all judges and administrators with a hyperlink to the article and included a printed copy in conference materials.

In addition to having basic definitions and concepts, we decided it would be helpful for judges and administrators to have a good tool to assess where they stood with regards to procedural fairness in their courtrooms and court houses. We searched for a means to allow and encourage them to measure their effectiveness. Through the assistance of a court educator in California, we found the answer in the report published in 2011 by the Center for Court Innovation on research conducted on procedural fairness in California: PDF. We are grateful to Ms. Diane Cowdrey and Mr. Douglas Denton of the California Administrative Office of the Courts for sharing this report.

Besides a wealth of information, tools, techniques and suggestions, this report contains a self-assessment for court leadership. We loved the idea of a self-assessment as an activity that would provide court officials with a means to see how procedural fairness impacts many aspects of their courts, as well as to get feedback about their effectiveness. They could also quickly see their strengths and weaknesses. The problem was persuading court officials to actually complete the survey.

In order to make it as easy as possible for the court officials, we worked with our web designers to transform the paper assessment into an online tool, accessible at any time, easy to complete, and providing instant results. Another benefit realized from this method was that the data from the survey fed a spreadsheet from which analysis could be made and shared. The online self-assessment became part two of the project, with the hope that it could also be a part five for officials willing to reassess themselves at a later date. The assessment gathered information on date of completion and court level, but was otherwise totally anonymous.

Over 200 judicial officers and court administrators completed the self-assessment, although not everyone completed it before the face-to-face session which constitutes part three. In addition to providing a contextual activity with feedback for participants, results of the self-assessment were used to guide the focus of part four of the learning series, a webinar, as will be explained below. Thus, parts one and two of the learning series provided in-depth background and context for the learning, as well as serving to inform judges of their own level of procedural fairness through an interactive activity.

With the way prepared for him, Judge Burke presented face-to-face sessions at two judges’ spring conferences as part three of the series. In April, he presented a 2-hour session to Washington’s Superior Court Judges and Administrators, an audience of close to 200 people. In June, he returned to the state to present to the District and Municipal Court Judges at their conference. We videotaped the June presentation so that anyone who missed the live conference session could also view it when they wished to do so. In June, the presentation lasted three hours and included a listening self-assessment for 175 audience members.

While Judge Burke is an important and well-known figure nationally, one of our goals was to involve local judges in the conference sessions to provide relevance. In order to do this, two judges from the Equity and Fairness Committee of the Superior Court Judges’ Association and two judges from the Diversity Committee of the District and Municipal Court Judges’ Association agreed to be videotaped during an entire half day while presiding in their courtroom. We shared the videotapes with Judge Burke, who subsequently worked with each of the four judges about what he saw in their videos and what techniques they could use to improve their fairness. During the live presentations, Judge Burke shared video of judges in other states, and led discussion and provided commentary on these videos. Next, the local judges testified as to how videotaping helped them, and what changes they planned to improve their procedural fairness. After the live session, judges had a solid understanding of what procedural fairness is, why it is important, how it can make a difference for them in their jobs every day.

The two conference sessions reached over 350 judges and court administrators and were highly rated for content and effectiveness. We also found that many more judges completed the online self-assessment after hearing the live presentation.

The goal of the fourth part of the learning series, the webinar, was to provide concrete steps for improving procedural fairness in areas Washington judges identified as being less developed in their courts. It would also serve as a reminder of what they had previously learned, and add to their knowledge of the topic. Finally, it would suggest activities for judges and administrators to undertake in order to get more feedback about their progress on procedural fairness in both court room and court house. In preparation for the webinar, we analyzed the results of the self-assessment to identify where Washington judges believed they needed the most help.

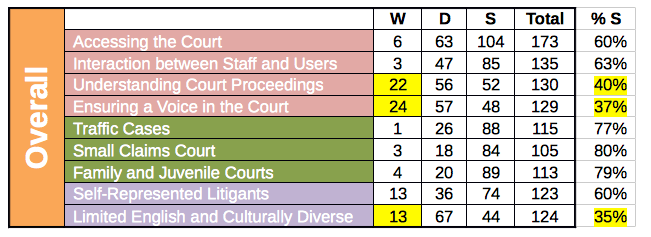

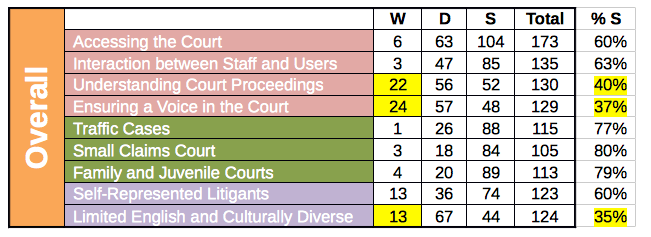

Table 1: Self-assessment analysis of responses for all courts completing the survey.

The table shows the nine areas of self-assessment as developed in the California Courts report. As can be seen, Washington judges considered themselves and/or their courts weaker in three areas, as indicated not only by the number of weak responses, but also by the lack of strong responses. These areas are Understanding Court Proceedings, Ensuring a Voice in the Court, and Limited English and Culturally Diverse. Due to time constraints, faculty for the webinar decided to focus in on the first two areas of need; another webinar is planned for the third area.

During the webinar, we showed clips from the Washington judges’ videotapes, and the judges themselves provided commentary related to the specific clips they chose. We also offered concrete activities that judges and administrators could do to gather feedback and make improvements in each of the focus areas. We polled the audience during the presentation to encourage them to seriously consider being videotaped and to discover their opinions on relevant topics. We also asked for their feedback using chat about steps they have taken or would like to take in their jurisdictions.

Sixty-five people attended the live webinar, called Procedural Fairness: Real Steps for Real Improvement, and another 80 have viewed the recording. According to polling taken during the webinar, 82% of participants said they are “very likely” to videotape themselves in order to see what they look like and how they sound to court users, while 18% said “maybe.” No one said they definitely would not be videotaped. Participants also shared many ideas they thought would work in their courts to improve procedural fairness. Participants overwhelmingly rated this webinar high. In applicability to their jobs, likelihood of implementing what they learned, increase in content knowledge level, and content delivery, over 90% agreed/strongly agreed in every case.

While our polling and evaluations indicate high interest and satisfaction with the learning they experienced about procedural fairness, we have no way of knowing how much change has actually occurred, or is occurring, because of participation in all or part of the learning series.

We do know several things:

- We reached many judges and court administrators through our efforts. Over 400 people participated in one or more of the components of the process.

- We did much more than simply present a conference session. We provided several concrete activities with opportunities for participation, discussion or feedback to help make the learning more real. We chunked up the content and spread it out over a five month timeframe.

- There is a “buzz” around Washington Courts on the topic. Anecdotally, the author has heard judges from several different court levels talking about incorporating aspects of procedural fairness into sessions at the Washington State Judicial College. In addition, several conference sessions are planned for spring 2013 that tie into the topic—judges have stated this while planning the sessions, and as a reason for having the sessions. “This will tie in well with what we learned last year about procedural fairness.”

- Concepts integral to procedural fairness are appearing in plans for reorganization of the Washington State Judicial Branch.

Will this learning series improve the public’s perception of procedural fairness in Washington’s Courts? One can always hope so. If nothing else, evaluations show that participants found the series relevant to their work, and they tell us they will apply what they learned in their jobs. If they follow through, positive change will occur.

References

Allen, I. E., Seaman, J. and Garrett, R. (2007) Blending In: The Extent and Promise of Blended Education in the United States, Sloan Consortium.

Burke, K. and Leben, S. (2007) Procedural fairness: A Key Ingredient in Public Satisfaction. The American Judges Association.

Edwards, E. (2012) Creating e-Learning that Makes a Difference, http://info.alleninteractions.com/?Tag=CCAF.

Tyler, T. R. (2006) Why People Obey the Law.

Porter, R. (2011) Procedural Fairness in California: Initiatives, Challenges, and Recommendations. Center for Court Innovation, New York, NY and Judicial Council of California/Administrative Office of the Courts, San Francisco, CA.

Smith, N. (2012) Blended Learning: Seven Lessons Learned through Experience, NASJE News, http://nasje.org/blended-learning-seven-lessons-learned-through-experience/.

NASJE member Nancy Smith recently moved from the Washington State AOC to the Pima County Superior Court in Tucson, AZ where she has assumed the position of Field Trainer. In this position, Nancy is responsible for providing training to six courts of limited jurisdiction in Pima County on topics such as the case management system, legislative changes, ethics and more. She has worked in judicial branch education since joining the Washington State Administrative Office of the Courts (AOC) in September 2008 as a Court Education Professional. She has worked in education for most of her career, including 14 years as a teacher at the community college and secondary levels in Tucson. Prior to moving into court education, she assisted the Deans of Curriculum at the Evergreen State College in Olympia, WA planning and producing the curriculum for Evergreen’s full-time programs. In a past life, she spent four years as an Army Intelligence Officer.

Ms. Smith has produced education events for judges and court staff at all levels and in several different formats, most recently adding eLearning to her repertoire. She completed a certificate in Electronic Learning Design and Development at the University of Washington. She has organized a variety of webinar and self-paced learning modules for different court groups. In 2009, Ms. Smith was awarded a grant from the State Justice Institute to establish a model for blended learning (combining e-learning with face-to-face learning) for Washington Courts. The Procedural Fairness learning series was the last project for the grant.

Ms. Smith has broad experience in multi-cultural education, and has traveled widely in the United States and abroad. A French linguist, she earned her bachelor’s degree from the College of William and Mary in Virginia, and her master’s in French Language and Literature from the Université Libre de Bruxelles in Brussels, Belgium. She is a certified community college and secondary teacher. She also studied Spanish at the University of Arizona. When not at work, she enjoys travel, gardening, and a variety of outdoor activities.